sydney operahouse

index

Persönliche Erinnerungen

Damals bei der Eröffnung 1973: Mein Bericht

Rekonstruktion 2020

Sydney's icon celebrates without hero of grand design

Architect comes out of retirement to shape Opera House's future

David Fickling in Sydney, The Guardian Saturday October 18, 2003

At the celebrations to mark the 30th anniversary of its opening tonight, the Sydney Opera House will be awash with ballet, opera, pop music and champagne.

Only one thing will be missing:

Jørn Utzon, the

Danish architect who designed it.

Two million people visit the iconic building every year, but Utzon has

never set eyes on his masterpiece. The Australian authorities have

tried everything to get the reclusive architect to return to the

building he left unfinished in 1966, after a falling-out with the New

South Wales state government. Plane tickets and cruise ships have been

suggested. A film producer even offered his two Gulfstream jets to fly

Utzon and his family to Australia, keeping below 18,000ft and stopping

as often as the architect wanted en route.

Tonight he will be present only in the form of recorded messages and

his son Jan, who is working with him on a A$70m (£28m) renovation of

the complex.

It is nearly half a century since Joern Utzon won the £5,000 prize

to design an opera house on the site of the old tramsheds on Bennelong

point. At the time he was a relative novice. According to legend, his

design was only pulled out of the stack of 233 other entries - which

included depressing functionalist boxes as well as one design shaped

like a gramophone trumpet - because of the enthusiastic support of the

Finnish modernist Eero Saarinen.

When work began in 1959 he still had little idea of how the cluster of

shells could be assembled. Originally he intended them to be made out

of wire mesh, but engineers said the structure would never hold

together. A flash of inspiration while toying with an orange led him to

design the sails' surfaces as segments of an imaginary sphere 150

metres (500ft) across. The decision allowed the engineers to cast

concrete blocks of the exact shape needed for the sails. The work was

still complex: at the time, Sydney had a single computer housed in a

city centre bank, and the design team had to visit it every time they

came up against a problem. The NSW government became increasingly

disenchanted with the project as time wore on. The lottery-funded

complex should have been completed in four years with a budget of A$7m,

a figure that the state premier, Joe Cahill, supposedly chose because

it was the most he could get through cabinet.

But it took 14 years and A$102m to complete the building. Mr Cahill,

expecting opposition from future governments, supposedly told Utzon to

dig as much earth and pour as much concrete as he could before another

premier could call a halt to the work.

Within a year of Mr Cahill losing the 1965 election, Utzon had walked

off the project after NSW's antagonistic new Liberal government refused

to pay his office fees. A team of novice Australian architects were

brought in to complete the building's much-maligned interiors. Even the

opera house's chief executive, Norman Gillespie, admits that their work

is "just awful". Few expected Utzon to return to a project loaded with

so much bitterness, especially after he retired in 1999. Promising

never to return to Sydney, Utzon had quietly burned his maquettes and

drawings in Denmark in 1968.

But just a few months after announcing his retirement he agreed to

start work on renovating the building, along with his son and the

Australian architect Richard Johnson. Jan Utzon said the changes were

needed to bring the building up to date.

"If you pull the brake at the status quo, then you might risk the

building dying out and becoming like a museum piece," he said. "We are

still dreaming up new things and hopefully making it better and better."

The plans are bold: there will be a colonnade inspired by Mayan temples

along the western edge of the building, with nine glass panels behind

it to open the building's basement theatre foyers up to the harbour.

On the opposite side a reception area will be redesigned as a concert

space, complete with a tapestry designed by Utzon based on the work of

Bach.

The bigger problems will come with the renovation of the opera

theatre itself. The space was designed as a drama theatre, and seats

just over 1,500 - just two-thirds of the size of the Royal Opera House.

The wings are so narrow that strips of foam have been taped offstage to

prevent ballet dancers crashing into the walls, and sets used for

touring productions from Melbourne's Victorian Arts Centre have to be

cut down to fit the stage.

Worse still, the orchestra pit is too small for the musicians needed

for performing grand opera. Extending the pit would mean cutting into

the tie beam, a vast underground chinstrap of concrete holding the roof

shells together. "Ten years ago nobody would have dared do that, but

with the technology now you can cut it and the shells will not collapse,"

Mr Gillespie said.

The work will require the opera theatre to be closed for a year, and

there are still bolder plans on the drawing board to drop the theatre's

floor and open up enough space to create a world-class hall.

Mr Gillespie said Utzon's absence would not dampen the celebrations.

"He doesn't need to come," he said. "Every inch of it is in his mind,

he knows it intimately. If you talk to him, it's as if he has been here."

Versöhnung mit Sydney

Jørn Utzons Interieur für das Opernhaus

Rudolf Hermann, in: NZZ 27.09.2004

Das Opernhaus

von Sydney ist ohne Zweifel die Architektur-Ikone

Australiens - von außen. Weil der Architekt Jørn Utzon 1966 das Projekt

vor der Vollendung im Zerwürfnis mit dem Auftraggeber, dem

australischen Gliedstaat New South Wales, verlassen hatte, wurde es im

Inneren nicht nach Utzons Intentionen vollendet. Doch 31 Jahre nach

seiner Einweihung hat der prominent am Hafen gelegene Gebäudekomplex

ein von Utzon entworfenes Interieur bekommen.

Nachträglich erweist es sich als Vorteil, dass der Reception Room trotz

prächtiger Aussicht auf das Hafenbecken immer ein Mauerblümchendasein

fristete. Mit einem grünen Teppich und schwerem Holztäfer war er dunkel

und für offizielle Empfänge wenig geeignet. Er wurde deshalb nur selten

benützt und auch nie modernisiert. Glücklicherweise, denn als vor fünf

Jahren Utzon auf Anfrage der Regierung von New South Wales zusagte,

Designprinzipien für eine Innenrenovation der Oper auszuarbeiten,

genügte es, den Teppich und die Holzverkleidung zu entfernen, um

vierzig Jahre zurückzublenden und Utzon die Gestaltung eines

Innenraumes nach seinen ursprünglichen Vorstellungen zu ermöglichen.

Was nun der Öffentlichkeit übergeben worden ist, ist allerdings nicht

Utzons Entwurf von 1965, sondern ein vom Architekten selbst behutsam um

seine Erfahrungen der letzten vier Jahrzehnte angereichertes Interieur.

Für Trevor Waters, den Projektleiter des Reception Room, zeigt Utzons

einziges (und einzig mögliches) Original-Interieur in der Oper, wie

visionär das ursprüngliche Konzept und wie perfekt Utzons Gefühl für

das richtige Material war. Der Boden aus Eukalyptus-Parkett hellt den

Raum auf, und die nunmehr aus klarem Glas bestehenden Fenster geben den

Blick auf das Wasser unverfälscht frei. Vor allem aber strahlen die

Sichtbeton-Balken eine ganz neue Atmosphäre aus. Schließlich

beherbergt der Utzon-Room (wie er zur großen Freude des Architekten

jetzt offiziell heißt) auch ein Unikat: eine vierzehn Meter lange und

knapp drei Meter hohe, von Utzon selbst entworfene Tapisserie.

Entstanden ist die von Musik und Malerei inspirierte Arbeit in

Zusammenarbeit mit Utzons Tochter Lin sowie Grazyna Bleja, der Leiterin

des Victorian Tapestry Workshop in Melbourne. Nun symbolisiert das Werk

die späte Versöhnung des Dänen mit Sydney.

Die Größe der kleinen Dinge

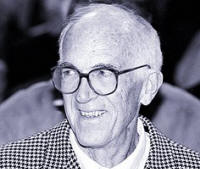

Zum Tod von Jørn Utzon, dem Erbauer der Sydney-Oper und Begründer der ikonischen Architektur

Gerhard Matzig (SZ, 01.12.08)

Sein weltberühmtes Werk, die Oper von Sydney, hat er nie in Vollendung erlebt. Wer aber bis zuletzt gehofft hatte, dass sich der dänische Architekt Jørn Utzon, der im April seinen 90. Geburtstag feierte, irgendwann doch noch mit dem fünften Kontinent und der Geschichte eines der bedeutendsten Bauwerke des 20. Jahrhunderts aussöhnen möge, muss diesen Wunsch nun endgültig aufgeben. Utzon starb am Samstag, 29. Nov. 2008, in Kopenhagen.

Als Utzon 1957 den Wettbewerb zum Neubau eines Opernhauses auf der Landzunge im Hafen von Sydney gewonnen hatte, musste sich die Öffentlichkeit erst danach erkundigen, wer denn dieser Utzon eigentlich sei. Der Sohn eines Schiffsbauers, der bei Asplund, dem Vater der modernen skandinavischen Baukunst, studiert hatte, war ein unbekannter Nachwuchsarchitekt, als seine suggestiven Skizzen von der neuen Oper für Furore sorgten. Mehr als ein paar Skizzen gab es allerdings auch nicht, als man in Sydney voreilig zu bauen anfing. Es war nicht mal klar, ob sich die charakteristische Silhouette der Betonschalen, die sich wie Segel über einem Plateau wölben, konstruktiv überhaupt verwirklichen ließen. Die Kosten schätzte man auf umgerechnet dreieinhalb Millionen Euro. Es wurden 50 Millionen. Und aus den veranschlagten sieben Jahren Bauzeit wurden 16 Jahre.

Endgültig fertig wurde die Oper erst im Jahr 1973. Schon 1966 hatte sich Utzon, ständig in der Kritik wegen steigender Baukosten und mangelnder Planungssicherheit, im Streit von dem Projekt losgesagt. Er verließ Sydney im Planungschaos und schwor sich, "niemals " nach Australien zurückzukehren. Vollendet wurde die Oper schließlich von anderen Architekten.

So erlebte er, in baulicher Vollendung, nie die perfekte Symbiose aus rationalen, nämlich konstruktiven Aspekten und gestisch wirksamer, lichtintensiver Raumkunst, durch die sich die Oper auszeichnet - und auch Utzons relativ schmales Gesamtwerk weithin überstrahlt. Für Utzon hatte die Form nicht der Funktion zu folgen, sondern es galt, Funktion und Form in Übereinstimmung zu bringen. In der Nachkriegsmoderne war er einer der wenigen Gestalter, der dem großen Missverständnis der klassischen Moderne ("form follows function") nicht erlag. Er selbst schrieb einmal: "Wenn Form und Funktion eines Raums harmonisch verschmelzen sollen, ist die Voraussetzung für gute Architektur ein Bedürfnis nach Behaglichkeit. So einfach und vernünftig ist das. Es setzt die Fähigkeit voraus, allen Forderungen nach Harmonie, die mit der Aufgabe verbunden sind, gerecht zu werden und sie zu einer ganz neuen Einheit zu bringen - so wie die Natur es macht."

Utzon war deshalb mit der "Muschelschalen"-Oper nicht nur ein Vorreiter des heute so modisch begriffenen organischen Bauens - sondern auch ein Mitbegründer ikonischer Architektur. Aber nicht um des Spektakels willen oder zum höheren Ruhm eines Label-Bauherrn, sondern aus einem schlichten Bedürfnis nach Raumkraft, Harmonie und Behaglichkeit. So einfach ist das - und so vernünftig.

Under full sail

Sydney Morning Herald, October 18, 2003

Boats crammed the harbour and people crowded the foreshores as the Queen opened the Sydney Opera House on October 20, 1973. Those who worked on and in that magical building share their memories of its first 30 years.

Geoffrey Rush, actor

In 1973 I was a fledgling actor with the relatively new Queensland

Theatre Company. A hippie intellectual, university graduate maverick

playing the greasepaint repertoire. Gough Whitlam was not long in. Oz

voices were loud and brash and playful. In plays and films and books.

It felt like a cultural fuse had been lit.

And the Opera House was opening. I made a traitorous pilgrimage to sinful

Sydney from the rigorous underground of the banana state and marvelled

at this strange new '50s Martian building the way I would marvel at the

Eiffel Tower a couple of years later when I became a student in Paris.

Something about architecture and curves.

The matinee of Jim Sharman's production of The Three-penny Opera made

me book straight back in for an evening show. Donald Smith, a former

Queensland canecutter with a harelip, sang in Pagliacci and it was the

first time ever in a theatre where I've wept, applauded, been

frightened, cheered and had a hairs-up-on-the-back-of-the-neck oceanic

sense of transcendence all at the same time.

In the papers, people complained that women's stilettoes were being

sacrificed on the presumably ill-thought-through granite forecourt.

Actors quite rightly whinged about the aesthetically compromised

debacle of the Drama Theatre. But in the subsequent decades I've played

there in Wilde and Chekhov and Gogol and have always thought it,

despite all, to be marvellous.

John Bell, artistic director, Bell Shakespeare Company

I read somewhere that Utzon had based the northern walkway of the Opera

House on the ramparts of Elsinore Castle. I haven't been able to verify

that, but it doesn't matter: when I was directing Hamlet earlier this

year I used to pace around the walkway late at night when it was

entirely deserted. I'd stare over the edge, watch the waves breaking

against the stone blocks and think, this is how Hamlet felt. Did I see

a ghost? Not really, but I know the place is full of them; they are the

memories of all the happy evenings I have spent in the Opera House.

Rolf Harris, entertainer

On September 28, 1973, I staged the first-ever performance in the

Concert Hall of the Sydney Opera House - three weeks before it was

officially opened.

In the '60s, while the Opera House was under construction, I had been

taken on a tour of the half-completed building by entrepreneur Jack

Neary. It was a stunning sight even then, and when I said I'd love to

perform there when it was finished, Jack said he'd do his very best to

make it happen. He was as good as his word.

Ernie Dingo, actor

I had seen pictures of the Opera House, the city in the background, the

Bridge in the foreground, but as a teenager, 30 years ago, it was a

long way away from Western Australia.

Nine years later I had the great fortune of acting on its stage in Jack

Davis's Dreamers in October, 1982. A whole month at the Opera House.

Walk to work. Round the corner at Circular Quay off George and there

she was. She looked like beautiful white swans in the late afternoon

light.

Everyone inside performed sacred rituals for those who came to see.

Musicians, dancers and actors all glorified by the workers who never

took their bows. Now they can raise their glass or stubby and give

three hearty cheers and say: "Thanks, mate. Job well done. Happy 30th

birthday." I know I will.

Ronald Prussing, principal trombone, SSO

The Sydney Opera House has loomed large in my life. I watched the

official opening from my father-in-law's apartment in Kirribilli and I

was fortunate enough to participate in the official opening concert by

the Sydney Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras.

It was an all-Wagner affair, with Birgit Nilson singing the Immolation

scene from Gotterdammerung, a role she had made famous both on stage

and on a recording with Sir Georg Solti and the Vienna Philharmonic.

During one of the rehearsals, the players thought they may be playing

too loud for Nilson. Mackerras responded with suitable contempt for our

concerns: "You will never drown her out - just keep playing."

Peter Kingston, artist

Back in the '70s, struggling through my first year in architecture

along with Jan Utzon at the University of NSW, I was invited to the

Utzon home at Palm Beach for an evening meal. It was exciting but what

I could possibly have to say to the great man. And what were we going

to eat? What would Danish food be like? I began to imagine a table full

of exquisitely prepared Danish delicacies presided over by the Utzon

women, Liz and Lin.

The family had an aura, they seemed beyond this

world. They were all as handsome as could be and extremely welcoming.

The food turned out to be battered fish and chips from the local

takeaway and much enjoyed. Joern asked what I was studying and I

reluctantly told him architecture, adding that I had actually finished

an arts degree first. Joern was pleased. All architects should study

the humanities before tackling architecture, he said.

I never saw him again. We all sensed something pretty important was at

stake later when we marched up Maquarie Street to protest after Utzon

was forced out of the project. We all felt we'd let him down badly.

The added tragedy was that Utzon wanted to make this place his home.

Just think of the wonderful national art gallery and parliament house

we might have had.

As an artist today, I find the Opera House almost

impossible to capture. But I keep on trying. Best viewed from the

Cahill Expressway, where the mutilated bits are hidden, it's always

different and, like nature, takes on what is happening with the light

all around it. Lloyd Rees captured it best when he merely indicated it

on the right-hand side giving centre stage to a massive burst of light

through the clouds onto the water, which he'd experienced while riding

the ferry into Circular Quay.

Yvonne Kenny, singer

The first official opera performance in the Opera Theatre of the Sydney

Opera House was Prokofiev's War and Peace performed by The Australian

Opera in the opening season in 1973. However, before that, in July

1973, I was part of a "trial run", to give staff an opportunity to test

the stage mechanics and lighting.

Two one-act operas were performed to paying audiences by the Opera

School of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. The pieces were Larry

Sitsky's The Fall of the House of Usher (based on the story by Edgar

Allen Poe) and Dalgerie by James Penberthy, the story of a young

Aboriginal girl and her love for a station manager. I remember the

incredible excitement I felt as a young opera student, going into that

magical building for the first time.

I played the sister in The Fall of

the House of Usher with John Wood as my twin brother and John Main as

the narrator. The need for a trial run for the Opera Theatre became

apparent, when on our first performance, the stage machinery jammed

making it impossible to change the set. We performed the piece on an

empty stage in full working lights - not quite the required atmosphere

for a ghoulish ghost story!

The second piece, Dalgerie, included a group of Aboriginal dancers who

had travelled from Arnhem Land. I remember being fascinated by their

music and dances, which included a traditional fertility rite. I have a

clear image of us all sitting together in the green room backstage and

sharing a remarkable moment in the history of our country. What an

entirely appropriate choice it was for the first operatic performance

in the new house.

Jack Mundey, unionist

I worked on the Opera House in 1959-60 as a builder's labourer. In 1962

I was elected an official of the NSW Builders Labourers Federation and

secretary in 1968, so I had a very intimate connection with it during

those turbulent years.

During the '60s and '70s, the Opera House workers were involved in many

political campaigns, including those against the Vietnam War and

apartheid in South Africa.

Paul Robeson, the American singer and peace activist, was the first

artist to perform on the site when he sang for a lunchtime audience of

workers. The BLF also brought Doreen Warburton's Q Theatre to the Opera

House workers. Jim McNeil's play, The Chocolate Frog, about life in

prison, was the first play performed for the workers at lunchtime on

the site.

When it was nearing completion, I said to one of the workers who'd been

there since the first day: "You have had a good run, Giuseppe. Fourteen

years is a long time for a building worker to be on the one site."

"Yes, Jack," he replied, "though don't you think we should build

another one at Kirribilli, looking back this way. Only one looks a bit

lopsided."

I successfully campaigned for 100 workers to be invited to the Opera

House opening. Sir Robert Askin introduced the Queen, and we cheered

Gough and Margaret Whitlam as they alighted from a boat at Man O'War

steps. Someone asked Sir Robert how Gough was arriving from Kirribilli.

Sir Robert replied, "Let him walk across." I hope the workers

who built this special building will be remembered 30 years on.

Brett Sheehy, director, Sydney Festival

For 18 years I've been so lucky to be with companies performing in and

around this, the most beautiful building on earth. But it is the Sydney

Festival's panoply of events, inside and outside the House, which has

brought me the greatest pleasure.

We've helped bring brand new audiences into the House (I have never

seen such a mix of patrons as the Deep Purple fans, the george fans and

the Sydney Symphony Orchestra fans, who all rubbed shoulders in the one

concert experience during the 2003 Festival); that we've helped make

the forecourt a natural performance arena for this city; and that we've

had the privilege to call the House "the Home of the Festival".

But for all the hundreds of thousands of people we've played to, no one

has moved me as much as the little girl - five years old - who'd come

from Bass Hill with her grandma to see Transe Express's Celestial Bells

on the forecourt last year. They sat in front of me and at the end of

the show, the little girl said: "Grandma, I love you for bringing me to

this, I won't forget it until I'm grown up at least."

That experience cost them the price of a couple of bus tickets and yet

it lifted their hearts beautifully. It gets no better than that.

David Williamson, playwright

When the Sydney Theatre Company does my latest play, Amigos, in the

Drama Theatre of the Opera House in April next year, it will be the

15th of my plays that have been performed in that great edifice. I

consider this an incredible privilege.

The Opera House is one of the supreme imaginative achievements of the

20th century and what artist wouldn't want to be part of its repertoir?

One can be struck mute on a sunny afternoon as its glistening white

tiles effortlessly proclaim its formal beauty, but some of the great

nights of my life have been relaxing with the cast after the tension of

an opening night in the green room backstage, probably the shabbiest

area in the whole edifice.

Its battered old sofas and chairs convey little or no hint of the

grandeur of the exterior, but after the show is finally on the road,

it's where we all head. And it's where the tensions of the actors, the

director, the crew and the playwright dissipate.

Actors have always been very special people to me. Before they bring

their huge talents to bear, all I have is words on a page, so it's with

a very special feeling of affection and privilege that I've shared

those green room nights with them. Their gallows humour is something

akin to soldiers who've been under intense fire on a battlefield and

survived, except that the quality and timing of the anecdotes is

considerably better than your average footsoldier's.

So when someone mentions the Opera House, the first image that hits me

isn't those majestic sails we've seen on a thousand postcards, but a

cavernous pit made resonant in my memory by a legion of wonderful

actors letting off steam. Loudly.

Richard Tognetti, artistic director, Australian Chamber Orchestra

There is a particular smell backstage at the Opera House. Like all

smells, it is exaggerated by nerves. I recall the fear and excitement I

felt as a student walking through the backstage rabbit warrens of the

SOH imagining that I would be performing in an important concert on the

Concert Hall stage later that night.

As practice rooms at the old Conservatorium were hard to procure, I'd

sneak into the House to practise. During my practice sessions I'd

imagine I was getting ready for these concerts and it was a thrilling

feeling.

Now performing at the SOH is a regular actuality yet the thrill and the

smell remain. Promenading towards those big sails (or curled orange

peel), climbing the stairs and waiting for that green light to go on at

the side of the stage and getting the "GO" from the stagehands, one

feels like a Formula One driver leaving the pit.

Die schönste Mehrzweck-Halle der Welt

Vor 30 Jahren öffnete Sydneys Oper. Erst jetzt werden die ambitionierten Pläne für das Haus vollendet

Von Michael Lenz, in: Berliner Zeitung, 21.Okt. 2003

SYDNEY, 20. Oktober. Der prächtige Bau schmückt das ganze Land. Wann immer es in Australien etwas zu feiern gibt, bildet Sydneys Opernhaus dafür die prächtige Kulisse. Silvester, Olympia oder - wie zuletzt - die Eröffnung der Rugby-WM immer steht Sydney Opera auf der Einladungskarte. Nun feiert das markanteste Bauwerk des Landes seinen 30. Geburtstag. Seine ganze Schönheit entfaltet das an drei Seiten von Wasser umgebene Opernhaus im Zusammenspiel mit seiner Umgebung: der stählernen Hafenbrücke, der Glasgiganten von Sydneys Innenstadt, dem Grün der Royal Botanical Gardens, dem Blau des Himmels und der strahlenden Sonne. Die weißen Segel seiner Dächer erscheinen von jener Leichtigkeit, die dem Lebensgefühl der Australier entspricht.

So ist Sydneys Oper längst zum festen Bestandteil des Selbstbewussteins des Landes geworden. Auch des politischen Selbstbewusstseins. Etwa vor drei Jahren als Ort des Corroboree - die symbolische Versammlung zur Versöhnung des weißen und schwarzen Australien. Oder vor einem halben Jahr, als es Gegnern der australischen Beteiligung am Irakkrieg gelang, in leuchtend blutroter Farbe den Slogan "No War" - kein Krieg - auf eines der steilen Segeldächer zu schreiben. Sydneys Opernhaus ist der Treffpunkt des Landes. Im Edelrestaurant "Bennelong" in der kleinsten der drei Hallen, die neben der eigentlichen Oper und der Konzerthalle das Ensemble Opernhaus ausmachen, bereiten sternengekrönte Spitzenköche die Speisen zu. Die Liste der Stargäste auf den Bühnen des Hauses liest sich wie ein Who's who der zeitgenössischen Kultur. Dort traten so illustre Künstler auf wie der Dirigent Leonard Bernstein, die Jazzmusikerin Ella Fitzgerald, der Tänzer Michael Barischnikow, die Bee Gees und die australische Operndiva Dame Joan Sutherland. Aber auch Kaliforniens neuer Gouverneur Arnold Schwarzenegger feierte dort Triumphe. Der nämlich gewann 1980 in der schönsten Mehrzweckhalle der Welt seinen letzten Body-Builder-Titel als Mr. Olympia.

Mit Ausstellungen, Partys und Konzerten feierten die Australier am Montag nun den 30.Jahrestag der Eröffnung des Bauwerks. Und ein wenig mit Wehmut. Mit gutem Grund. Erst im April dieses Jahres war sein Schöpfer, der Däne Jørn Utzon, für sein Lebenswerk mit dem Pritzker Award ausgezeichnet worden, dem angesehensten Architekturpreis der Welt. "Das Opernhaus von Sydney ist sein Meisterwerk und eines der großen Kultgebäude des 20.Jahrhundert - ein Symbol nicht nur für die Stadt, sondern für das ganz Land und den Kontinent", hieß es in der Laudatio. Der Preis war eine Genugtuung für den mittlerweile 84-jährigen Utzon. Heftig war er einst in Australien für seine ambitionierten Pläne kritisiert worden. So heftig, dass er 1966 - sieben Jahre vor Vollendung des Opernhauses - das Land verließ und in seine dänische Heimat zurückkehrte. Die hohe architektonische Auszeichnung versöhnte ihn zuletzt mit seinen australischen Kritikern. Zumindest aus der Ferne. Denn Utzon ist die Reise zu den Jubiläumsfeiern nach Australien zu beschwerlich. Sein Sohn wird ihn bei den Feierlichkeiten vertreten. Und er wird an einen Satz seines Vaters erinnern. Der sagte einmal: "Was für mich zählt, ist, dass die Menschen von Sydney die Oper lieben."

Vielleicht werden die Menschen von Sydney die Oper bald noch mehr lieben. Das enge, muffige Innere der Oper soll endlich nach Utzons ursprünglichen Plänen umgestaltet werden. "Utzon liefert uns die Designprinzipien, auf deren Grundlage Architekten in den kommenden Jahrzehnten arbeiten können", freut sich Joes Skrzynski, Vorsitzender des Sydney Opera House Trust. Damit wäre die Versöhnung Utzons mit Australien komplett. Immerhin die Vielfalt der Nutzung und Nutzer seines Bauwerkes stimmt Utzon heiter. Er sagte einmal: "Was für mich zählt, ist, dass die Menschen von Sydney das Haus lieben."

Rückbau ab Sommer 2005

Mit einem umfassenden Innenumbau des Opernhauses von Sydney im

nächsten Sommer soll das lang andauernde Zerwürfnis zwischen dem

85-jährigen dänischen Architekten Jørn Utzon und den australischen

Behörden endgültig beendet werden. Der zur Mitarbeit eingeladene Utzon

wird den Umbau von seinem Wohnsitz auf Mallorca aus leiten. Ziel der

Intervention ist neben der Verbesserung der Akustik eine Anpassung des

Innenausbaus an die ursprünglichen Pläne. Utzon hatte 1957 die

Ausschreibung für das Opernhaus am Hafen von Sydney gewonnen. Nach

einem Zerwürfnis mit der Bauherrschaft verliess er 1966 Australien für

immer. Dies führte zu einer Umänderung der Pläne für den Innenausbau

des 1973 eingeweihten Musentempels. (NZZ 13.Feb.2004)

Schiff mit zehn Segeln: Australiens "Taj Mahal"

Eindrücke von der Eröffnung im Oktober 1973

von Georg-Friedrich Kühn, für u.a. ARD-Hörfunk, Opernwelt und Frankfurter Rundschau im Oktober 1973

Publicity-Manager David Brown nannte es die „wahrscheinlich

letzte große Extravaganz“ unseres Jahrhunderts. Und in der Tat:

extravagant ist die Architektur, extravagant sind die Kosten. Rund

400 Millionen DM [200 Mio €] waren zu berappen für „Australiens Taj

Mahal“, zu vier Fünfteln aufgebracht in jahrelang veranstalteten

Lotterien, der Rest finanziert aus Steuermitteln.

Gleich einem Schiff mit zehn weißen Segeln liegt es verankert zu Füßen von Sydneys Wolkenkratzer-Stadtlandschaft in der Hafenbucht, malerisch hingeschmiegt auf eine Landzunge, die als prosaischer Straßenbahn-Terminal diente und heute benannt ist nach dem australischen Ureinwohner Bennelong. Der wurde von seinen Stammesbrüdern einst zum Fürsprech ernannt ihrer Belange gegenüber den eroberungslüsternen Engländern unter dem Kommando von James Cook. „An Plätzen wie diesen haben die Alten früher ihre Tempel gebaut“, soll Architekt Jørn Utzon gesagt haben, als er erstmals den Platz zu sehen bekam, auf dem das Sydney Opera House errichtet wurde; und was er in seinen ursprünglichen Skizzen avisiert hatte als Opernhaus, war tatsächlich Tempeln nachempfunden: denen der Mayas, deren Kultur Utzon kurz vorher auf der Halbinsel Yucatan studiert hatte.

Über eine riesige Freitreppe aus rötlichem Granit – auch als Theaterplatz nutzbar – gelangt man in die beiden Haupthallen des Gebäudes, im Innern weiter ansteigend zu den Rängen und zur verglasten Cafeteria mit Hafenblick: ideales Ambiente in den Pausen von Opern-, Konzert- und Theateraufführungen. Denn alles drei kann man in diesem Kultur-Zentrum genießen – und nicht nur das. An spielfreien Tagen können die verschiedenen, insgesamt sieben, Aufführungsräumlichkeiten – ausgestattet sämtlich mit simultanen Übersetzungsanlagen -, die Foyers und die beiden Restaurants auch privat gemietet werden für Feste und Kongresse. Ein reiner Musentempel ist Utzons Bau also nicht. Er wäre in Australien auch nicht auslastbar. Das Land, der Kontinent ist erst auf dem Weg, sich zur Kulturnation zu mausern. Und dass es erst sich auf diesen ambitionierten Weg begibt, - daran liegt es, wenn die ursprünglichen Visionen des dänischen Architekten verwässert oder, wie manche meinen, ins Gegenteil verkehrt wurden. Spötter rufen gar nun, da das Opernhaus gebaut ist, nach einem richtigen Opernhaus, in dem man wirklich alles spielen kann. Denn was äußerlich als genialer Wurf erscheint, ist in seinem Innern nur ein Kompromiss.

Als 1957 die Regional-Regierung von New South Wales die Architekten zum Wettbewerb aufrief, kürte die dazu bestellte Jury Utzons Skizze, die eine große Halle vorsah, universal nutzbar für Oper und Konzert, und eine kleinere fürs Schauspiel. Zu bauen begann man das ehrgeizige Projekt noch bevor alle Details vorgeplant waren 1959, und als nach ungeheuren Schwierigkeiten mit der Statik der 27.000 Tonnen schweren Beton-Segel-Dächer die endgültige Innenarchitektur festgelegt werden sollte, erwies sich die größere Halle als immer noch zu klein für die Bedürfnisse von Australiens Staatlicher Rundfunkgesellschaft ABC, deren Sydney Symphony Orchestra in die Halle ziehen sollte und für ihre Symphonie-Konzerte eine Reprise sparen wollte. Nur für 2.000 statt der geforderten 2.800 Besucher wäre Platz gewesen.

Australiens nationale Wanderoper andererseits, avisierter Mitmieter und damals noch in den Kinderschuhen, konnte eine abendliche Füllung des Raums nicht garantieren. Und so wurde die größere der beiden Hallen als reiner Konzertsaal mit 2.700 Plätzen ausgelegt, die „Australian Opera“ musste in die kleinere Halle mit maximal 1.500 Plätzen weichen, das Sprechtheater wurde ins Souterrain verbannt (550 Plätze). Die schon bestellte und bezahlte Bühnenmaschinerie fürs große Haus wurde erst gar nicht ausgepackt. Die Opernleute haben sich herumzuquälen mit einer viel zu kleinen Bühne. Es gibt keine Seitenbühne, Verwandlungen kann man lediglich per Drehbühne ausführen, was den Inszenierungsstil beeinträchtigt. Im Orchestergraben haben maximal 75 Musiker Platz.

Utzon hat diese Schildbürgerstreiche nicht zu verantworten. Schon 1966 zog er sich aus den Planungen zurück und will sich gar nicht mehr mit dem Bau identifizieren. Ein australisches Architektenteam leitete den Innenausbau – mehr schlecht als recht, wie viele meinen. „Pathetisches Dekor“, schrieb der Architektur-Kritiker des Time-Magazin. Und auf die Dysfunktionalität der Raumplanung anspielend, sprechen manche von einem „Desaster von Anfang an“, halten es „schlechthin für einen Skandal“, dass trotz der verausgabten Dollar-Millionen die Australische Nationaloper nun doch nicht die Heimstätte zur Verfügung hat, die sie bräuchte, um sich zu einer international respektierlichen Truppe zu entwickeln [was man aus der Sicht des Jahres 2003 dann so glücklicherweise doch auch nicht mehr sagen kann].

Durch die Entfernungen vom internationalen Austausch weitgehend abgeschnitten – Aushilfen können nicht binnen Stunden eingeflogen werden – ist die Entwicklung eines leistungsfähigen Opernensembles dort aber zusätzlich behindert durch mangelnde Kontinuität. Zum mindesten in der Vergangenheit. Inzwischen kann die Truppe zum Teil hervorragende Sänger beschäftigen samt Chor und Orchester – allerdings ohne Bindung an ein festes Haus mit gesicherten Probenräumen. Nur etwa drei Monate im Jahr kann in Sydney gespielt werden. Den Rest der Zeit ist man auf Reisen zwischen Adelaide, Brisbane, Hobart (Tasmanien) und Perth. Das erlaubt nur ein eingeschränktes Repertoire, kostet Spesen, Kraft und Nerven.

Dennoch ist man nicht pessimistisch über die künftigen Möglichkeiten. In den übrigen Provinzhauptstädten entstehen (oder sind gebaut) neue Theater, wesentlich billiger als der Pracht- und Sorgenbau an Sydneys Harbour Bridge, dafür effektiver nutzbar. Die Abonnentenziffern steigen und auch die staatlichen Subventionen. Mehr als die Hälfte ihres 14-Mio-DM-Etats [7 Mio €] fließt der Truppe aus öffentlichen Mitteln zu. Ein weiteres Zehntel sponsort die Industrie, die das Opernhaus als repräsentatives Werbesymbol entdeckt hat. Sogar Opern-Aufträge an heimische Komponisten konnten jetzt vergeben werden.

Zur Eröffnung gab’s freilich eher Bewährtes mit den Puccini-Einaktern des Triptychon. Für Turbulenz sorgte der Schlussteil Gianni Schicchi. Zu Szenenbeifall verlocken ließ sich das Publikum durch das prachtvolle Bühnenbild des Mittelstücks Suor Angelica mit seinen golden schimmernden, Licht durchfluteten Prunkräumen. Szenenbeifall gab es ebenfalls im zweiten Bild von Prokofjews Krieg und Frieden, wenn im dank der Bühnenmaße freilich etwas beengten Petersburger Ballsaal die Damen und Herren zum Walzer die Arme sich reichen. Auftrittsapplaus einheimsen konnte auch Birgit Nilson, als sie in rosaroter Seidenrobe zum Premierenkonzert antrat: „doch eigentlich noch recht jugendlich aussehend“, wie die Presse befand. Dass das Operntheater allerdings in schlichtem Schwarz gehalten ist, fand wenig Beifall beim Publikum.

Nicht rechtzeitig zur Eröffnungssaison kam man zurande auch mit der Uraufführung einer bereits fertig gestellten Oper über Riten der Aborigines von Peter Sculthorpe, Rites of Passage; die Premiere soll im Frühjahr nachgeholt werden. Zur Uraufführung programmiert ebenfalls zwei weitere Kurzopern: Lenz von Larry Sitsky (nach der Büchnerschen Novelle) und Felix Werders Affäre. Und dann erwartet man für dieses Jahr auch noch Australiens Star-Sopranistin Joan Sutherland, damit sich erfülle, was die Kulturplaner von dem Segelbau am Bennelong Point erhoffen: dass er zum Attraktionspunkt internationaler und heimischer Künstler sich kristallisiere down under.